A tale of two toilets

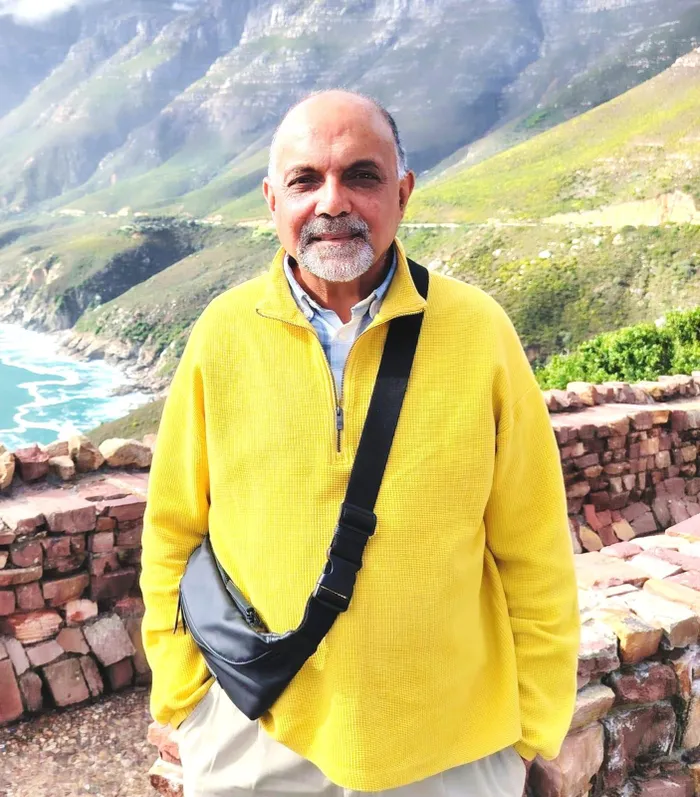

Mansoor Jaffer has been a lifelong activist for social justice.

Image: Supplied

Mansoor Jaffer is a writer, musician, and, over the past 18 years, he has played a leading role in the Cape Cultural Collective. This organisation promotes inclusion and development through the arts. He was a lifelong activist for social justice. Having worked in media as the former deputy editor of Cape Community Newspapers and in communications for most of his career, the Wynberg resident was also actively involved in the liberation struggle. He shares a prison story.

Pollsmoor Maximum Security is a cold and alienating space. And brutally lonesome when you are in solitary confinement.

We were there for a few weeks in September and October 1985, plucked from our homes in the dead of night by scores of armed police and detained under Section 29 of the Internal Security Act. The act provides for your indefinite detention without trial, with no access to visitors or legal representation.

Other detainees in our section included Dullah Omar, Christmas Tinto, Mountain Qumbela, Trevor Oosterwyk, Joe Marks, Saleem Badat, Yusuf Adam, and Wilfred Rhodes. Each was in a small single cell.

Solitude became our daily experience, broken only by an hour’s exercise in the prison yard where inmates on the other side of the building would shout all kinds of greetings, questions, and profanities at you.

Foreigner's I Wanna Know What Love Is blares out from the loudspeakers. A weather-beaten prisoner with a damaged eye washes the windows on the south side of the yard.

In my tiny cell, there are long periods when all one hears is the turning of keys, the clang of the prison doors, and the light footsteps of a warden doing his rounds. The lights in the cell remain on 24 hours a day.

One morning, after reading the story of Cain and Abel in the Bible and reciting a few passages from the Quran, I carefully followed the journey of an ant as it made its way around my cell. This exercise lasts for about 30 minutes or so, until the little insect scurries away under the door.

My bed, a thin mat with two grey prison-issued blankets, is placed neatly on the cold concrete floor. A little basin with a cloth and soap lines the back of the accommodation PW Botha provided. I wait for lunch to arrive. It’s usually samp served with mashed vegetables in an aluminium plate.

Remarkably, these circumstances unleash the full spectrum of one’s imagination. My mind turns to the story of a prison movie I watched in my youth. Steve McQueen plays Papillon in the film by that name. Serving time for murder, he plots his escape from a South American jail. I vividly recall a scene where Papillon communicates through the toilet pipes with another prisoner, possibly played by Dustin Hoffman.

My mind is immediately made up. I was going to attempt this at Pollsmoor. The next day, I write a note to my fellow detainee in the cell next door. The messenger assigned to deliver the note is a heavily-tattooed prisoner doing cleaning duties in our block. I had previously slipped him some money to get me something to read.

That time, he delivered a Cape Times and Huisgenoot. I shed a silent tear when I read an article that a large group of women, which included my mother and wife Kay, had marched on Caledon Square to demand our release.

In my note to Llewellyn MacMaster, who was then the president of the SRC of the University of the Western Cape, I advise that he clear all the water from his toilet pot just before 5pm the following night. This was the time the warder goes off duty and a new one began his shift. For about 30 minutes, there were usually no cell inspections.

I had never met Llewellyn, but only knew of him from newspaper articles. I clean and flush my toilet well before the deadline. The aluminium cup removes lots of the water while a brown cloth absorbs most of what remained.

Exactly at 5pm, I went on my knees in front of the toilet pot. I feel both anxious that I would be found out and foolish at attempting something I witnessed in a movie some 12 years before. "Hello, Hello, Hello," I say. "Anybody there?" I repeated this for a few minutes before deciding I would abandon this exercise in futility.

As I was getting up, a voice came booming through the metal toilet, rising like a clear message from the deep.

"Greetings, comrade Mansoor, can you hear me?" The sound is crystal clear, better than anything Vodacom or Cell C are able to offer.

I drop to my knees again, my heart pounding heavily. The mildly unpleasant odour of the toilet reaches into the inner passages of my nostrils. But the excitement and thrill of the moment block out everything.

We talk for a good while, getting to know about each other’s families and histories. Our call ends when we hear the shuffle of the new warder who was starting to embark on his rounds.

He would be bearing a clipboard and pen and arrive at each of our cells, giving us a vacuous stare through the tiny windows of our 2m x 2m cells. And then he would be on his way to his little office down the corridor.