Book review: Fi, A memoir of my son

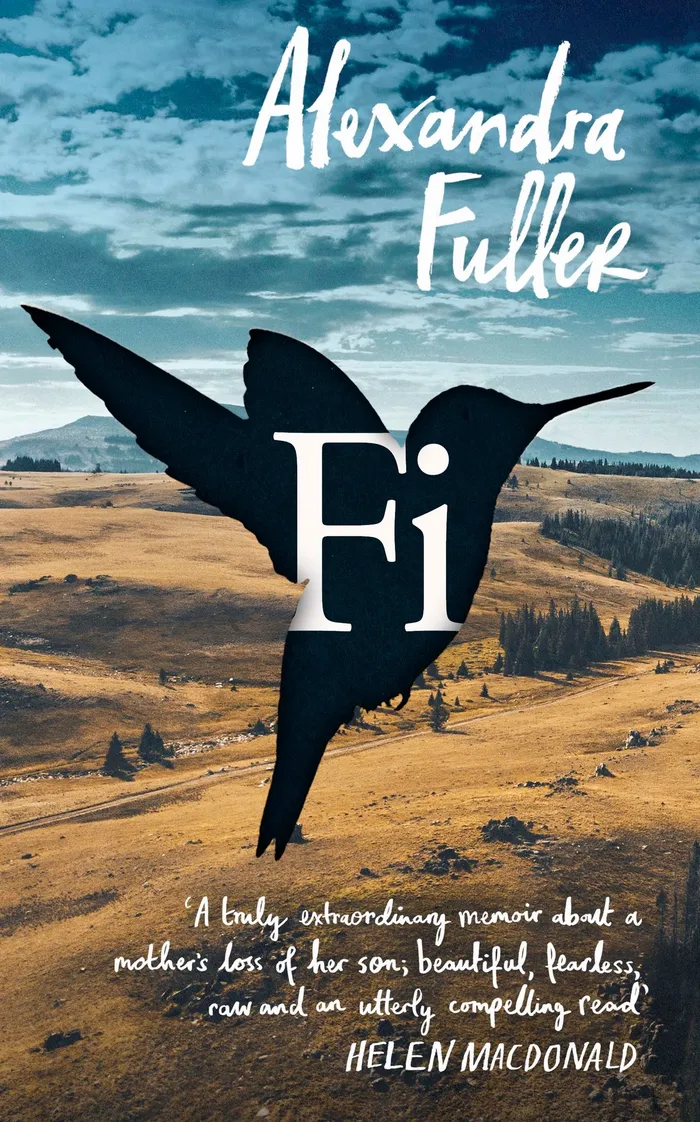

Fi, A memoir of my son

Alexandra Fuller

Pan Macmillan

Review: Karen Watkins

It must be one of the worst things in the world to deal with - losing an offspring, sibling, a close family member - especially for the mother.

Writing a memoir after losing her son must have been therapeutic for Fuller but publishing the book is not a good idea. Why pass on your grief to your readers?

Almost 50 and reeling from a mid-life breakup with “the glassblower”, as she calls him, grieving the death of her father and pining for her home country of Zimbabwe, she is finding her way through a volatile new relationship with a younger woman while vowing to get herself back on even keel moving into a small grotty condo.

And then, suddenly and incomprehensibly, her 21-year-old son Fi, dies in his sleep from a seizure.

The book is about how his mother and two sisters recovered from the shock and started living again. Living in a small town in Wyoming when everyone knows everyone else must have been difficult, greeted by sadness and memories around every corner.

Fuller is painfully aware that she cannot succumb and abandon her two surviving daughters as her mother before her had done.

From a sheep wagon deep in the mountains of Wyoming to a grief sanctuary in New Mexico to a silent meditation retreat in Alberta, Canada, Alexandra journeys up and down the spine of the Rocky Mountains in an attempt to find how to grieve herself whole.

There is no answer, and there are countless answers – in mediation, poetry, rituals and routines, in nature and in the indigenous wisdom she absorbed as a child in Zimbabwe.

Weaved in is her childhood in South Africa and all the people and rituals that got her through the first months and year.

It took some time getting into her writing style; incoherent, short sentences almost like notes of consciousness. I found myself skim-reading parts of it, not wanting to bring myself down into depression despite the tender reflections on her playful and strong philosophy of parenting, her deep friendships and how these friends gathered around to build her up and emotionally support her. This book is overly self-indulgent, not enjoyable in the way her other work is enjoyable, for obvious reasons; instead, we're served a double-helping of wisdom.

Fuller was born in England in 1969. She moved to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) with her family when she was two. After that country’s war of independence (1980) her family moved first to Malawi and then Zambia. She moved to America in 1994. Her book Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight won the Winifred Holtby Memorial Prize in 2002 and was a finalist for the Guardian First Book Award.